|

Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana Volumen 75, núm. 3, A140723, 2023 http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2023v75n3a140723

|

|

Continental mollusks from the Olmos Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Coahuila, Mexico

Moluscos continentales de la Formación Olmos (Cretácico Superior), Coahuila, México

Naylet K. Centeno-González1, Gerardo Zúñiga-Bermúdez1, Emilio Estrada-Ruiz1, Francisco J. Vega2,*

1 Departamento de Zoología, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Prolongación de Carpio y Plan de Ayala s/n, 11340, CDMX, Mexico.

2 Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510, CDMX, Mexico.

* Corresponding author: (F.J. Vega) This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How to cite this article:

Centeno-González, N.K., Zúñiga-Bermúdez, G., Estrada-Ruiz, E., Vega, F.J., 2023, Continental mollusks from the Olmos Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Coahuila, Mexico: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 75 (3), A140723. http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2023v75n3a140723

Manuscript received: February 24, 2023; Corrected manuscript received: July 12, 2023; Manuscript accepted: July 17, 2023.

ABSTRACT

We describe freshwater mollusks from the Olmos Formation, Campanian, Upper Cretaceous. The results were obtained from several specimens of mollusks, identified with two families of gastropods: Viviparidae (Viviparus sp.) and Physidae (Mesolanistes sp.), and three families of bivalves: Limidae (Pseudolimea sp.), Unionidae (Proparreysia sp., Unio sp., Unionelloides? sp., Plesielliptio sp., and Ostreidae (Ostrea sp.). Based on this taxonomic recognition, along with the associated fossil flora, it was possible to get a preliminary of the environment where the mollusks lived. The interpretation of the paleoenvironment resemble freshwater bodies adjacent to an estuarine system. Furthermore, the mixing of specimens of brackish and freshwater environments is indicative of a transport of some of these mollusks. The general view of the paleoenvironment where the mollusks inhabited is that of a transitional freshwater-estuarine in the Olmos Formation during Campanian times.

Keywords:Mollusca, Campanian, Olmos Formation, NE Mexico.

RESUMEN

Se describen moluscos de agua dulce de la Formación Olmos (Campaniano) del Cretácico Superior. Como resultado se obtuvieron varios ejemplares de moluscos, identificando dos familias de gasterópodos: Viviparidae (Viviparus sp.) y Physidae (Mesolanistes sp.), y tres familias de bivalvos: Limidae (Pseudolimea sp.), Unionidae (Proparreysia sp., Unio sp., Unionelloides? sp., Plesielliptio sp. y Ostreidae (Ostrea sp.). A partir de este reconocimiento taxonómico, así los restos de flora associados, fue posible obtener una interpretación preliminar del ambiente donde vivieron estos moluscos. La interpretación del paleoambiente es semejante a los cuerpos de agua dulce adyacentes a un sistema estuarino. Además, la mezcla de ejemplares de ambientes salobres y de agua dulce sugiere que algunos moluscos sufrieron transporte en un ambiente transicional de agua dulce a estuarino en la Formación Olmos durante el Campaniano.

Palabras clave: Mollusca, Campaniano, Formación Olmos, NE de Mexico.

- Introduction

Mollusks are cosmopolitan invertebrates. Bivalves and gastropods live mainly in marine and freshwater environments (Donovan and Hensley, 2003; Checa et al., 2009; Smitha and Mustak, 2017). In Mexico, the fossil record of bivalves and gastropods date from the Paleozoic (Quiroz-Barroso and Perrilliat, 1997), and the Mesozoic (Stanley et al., 1994). In particular, the fossil record of these mollusks is more frequent in Cretaceous deposits from Baja California, Nuevo León, Chihuahua, Coahuila, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas, Querétaro, Jalisco, Michoacán, Guerrero, Puebla, and Chiapas (e.g. Vega and Perrilliat, 1990; Perrilliat et al., 2008; Vega et al., 2019). Despite the presence of Campanian continental mollusks in Coahuila, these are scarce in the Olmos Formation. The only formal report is that of the gastropod Tympanotonus cretaceus from the uppermost Olmos Formation (Perrilliat et al., 2008). T. fuscatus is a brackish gastropod, living nowdays in mangroves and lagoons along the West African coast (Dockery, 1993; Bandel and Kowalke, 1999; Reid et al., 2008). The Olmos Formation includes different sub-environments such as swamps, flood plains, interlocking rivers, and meandering rivers, derived from the epicontinental Cretaceous sea present in North America (Estrada-Ruiz et al., 2013). In addition, the formation has a great diversity of life forms, mainly composed of fossil plants similar to those found in tropical and paratropical rainforests (Estrada-Ruiz, 2009; Estrada-Ruiz et al., 2007, 2010, 2011; Centeno-González et al., 2019, 2021). Other organisms preserved in fine-grained sandstones of the Olmos Formation include fragments of Theropoda, Tyrannosauridae, Ankylosauria, Ceratopsidae, cf. Chasmosaurus sp., Hadrosauridae, tracks of turtles, crocodiles and small birds (Ojeda-Rivera et al., 1968; Silva- Bárcenas, 1969; Meyer et al., 2005; Torres-Rodríguez et al., 2010; Porras-Múzquiz and Lehman, 2011; Ramírez-Velasco et al., 2014; López-Conde et al., 2021).

We studied the freshwater mollusks from a coal-mine of the Olmos Formation in Coahuila, NE Mexico. Our principal aim was to contribute to the knowledge of the molluscan shells in the Upper Cretaceous of northern Mexico. Some plants were found associated to the mollusks here described.

- Geological setting

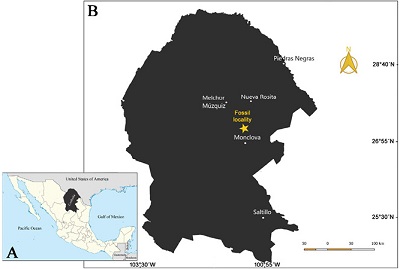

The Sabinas Basin includes mainly Upper Cretaceous strata subdivided in several lithostratigraphic units, among which the Olmos Formation includes of coal deposits extending to the north of Piedras Negras and the south of Monclova, between parallels 26° and 28° North and meridians 100° to 102° West (Weber, 1972) (Figure 1). The Campanian age of this formation is based on presence of ammonites (Flores-Espinoza, 1989), along with the presence of the lower Maastrichtian bivalves Exogyra costata and Pycnodonte mutabilis, collected from the base of the overlying Escondido Formation in Piedras Negras, Coahuila. The age was corroborated by means of U–Pb zircon methods (Campanian 76.1 ± 1.2 Ma) (González-Partida et al., 2022).

|

| Figure 1. Geographic location of Coahuila, Mexico, and sites where fossils were collected. A. Mexico, Coahuila is remarked in black. B. Coahuila, star = Tajo La Lulú, where most of the mollusks were collected. |

The Olmos Formation has a composed thickness of approximately 540 meters (Flores-Espinoza, 1989). It is represented by coal and a minor proportion of gray shale, carbonaceous shale, siltstone, and fine- medium-grained sandstone with parallel lamination and cross-stratification (Corona-Esquivel et al., 2006; Estrada-Ruiz, 2009). Initially, it was divided into five units (Robeck et al., 1956). Later, based on cores and stratigraphic and sedimentological studies from different quarries, the Olmos Formation was classified in two systems (Flores-Espinoza, 1989). The first and lower one is a delta plain, while the second and upper one consists of a river plain with river facies and flood plains (Flores-Espinoza, 1989). Later, Estrada-Ruiz (2009) described four depositional sub-environments: 1) Lithofacies A rich in coal, suggesting that they correspond to marshy areas with restricted circulation. 2) Lithofacies B composed of shales and sandstones, which might represent floodplain environments and/or lagoons with open circulation. 3) Lithofacies C from fluvial environment, probably with intertwined rivers, as suggested by the geometry of the sand bars and canal fillings. 4) Lithofacies D with sandstones with cross-stratification, interpreted as channel infills and lateral bars deposited in a meandering river (Flores-Espinoza, 1989; Estrada-Ruiz, 2009), where dinosaurs and Tympanotonus cretaceus were reported.

- Material and methods

A total of 44 samples with bivalves and gastropods were collected in sediments of the Olmos Formation in an open pit or coal mine known as Tajo La Lulú, with coordinates 27º 55’ 36.6 “N and 101º 11’ 30.2” W (Figure 1). All the samples come from a layer overlying the coal mantle, from where leaf and fruit impressions have also been reported (Estrada Ruiz, 2009). The material is deposited in the Paleontological Collection of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico City, under the acronym IPN-PAL. The fossils were cleaned with Dremel 290-01 electric hammer. For taxonomic recognition, the fossils were described according to their morphology. Later, we made a morphological comparison with similar fossil gastropods and bivalves (Lucas et al., 1995; Perrilliat et al., 2008; Taparila and Roberts, 2013). For a reliable identification, we used only complete specimens preserving ornamentation and other morphological features. The paleoenvironmental interpretation was based on the identified mollusks and comparison with close living representatives.

- Results

Systematic Palaeontology

Class Gastropoda Cuvier, 1797

Order Caenogastropoda Cox, 1959

Superfamily Ampullaroidea Gray, 1842

Family Viviparidae Gray, 1847

Subfamily Viviparinae Gray, 1847

Genus Viviparus Montfort, 1810

Viviparus sp.

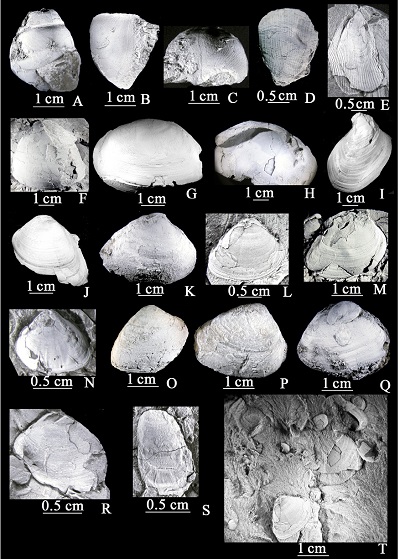

Figure 2A

|

| Figure 2. Samples of different freshwater species from the Olmos Formation. A. Viviparus sp. (IPN-PAL 207). B-D. Mesolanistes sp. (IPN-PAL 208, IPN-PAL 209, IPN-PAL 210). E. Pseudolimea sp. (IPN-PAL 211). F. Proparreysia sp. (IPN-PAL 212). G, H. Unio sp. (IPN-PAL 213, IPN-PAL 214). I. Unionelloides? sp. (IPN-PAL 215). J-R. Plesielliptio sp. (IPN-PAL 216 – IPN-PAL 224.). S. Ostrea sp. (IPN-PAL 225). |

Description. Small, pyramidal shell, only body and second whorls preserved; shell smooth, suture between first and second whorl weakly marked.

Material. One specimen, IPN-PAL 207.

Measurements. Length = 26.2 mm, width = 22.3.

Observations. Viviparus was very abundant in Cretaceous and Paleocene deposits of North America, specially in the Parras Basin, with specimens preserved in situ in red layers (delta plain) of the Paleocene Las Encinas Formation (Perrilliat et al., 2008).

Order Basommatophora Schmidt, 1855

Superfamily Lymnaeoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Physidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Mesolanistes Yen, 1945

Mesolanistes sp.

Figure 2B-2D.

Description. Medium to large, dextral shell, involute, with four convex whorls, the outer one being the most prominent; acute anterior, posterior almost flat; shell surface with longitudinal lines.

Material. Three specimens, IPN-PAL 208, IPN-PAL 209 and IPN-PAL 210.

Measurements. IPN-PAL 208, length = 29.4 mm, width = 32.4 mm, height = 13.3 mm (Figure 2B); IPN-PAL 209, length = 59.8 mm, width = 31.7 mm, height = 18.6 mm (Figure 3B); IPN-PAL 210, width = 18.3 mm, length = 15.0 mm (Figure 2D).

Observations. Mesolanistes was reported in deposits of the Upper Cretaceous of Sonora and other lithostratigraphic units in North America. In the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (late Campanian) it is very abundant, both in river deposits (green layers) and in marshes and lakes (Lucas et al., 1995; Perrilliat et al., 2008).

Class Bivalvia Linnaeus, 1758

Order Pterioida Newell, 1965

Superfamily Limoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Limidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Pseudolimea Arkell, 1933

Pseudolimea sp.

Figure 2E.

Description. Triangular shell, ornamented by strong and scaly radial ribs quite numerous.

Material. A left valve, IPN-PAL 211.

Measurements. Length = 24.6 mm, width = 18.0 mm.

Observations. Given the poor preservation of the specimen, it is likely that it has been transported from the coastal area.

Order Unionoida Gray, 1854

Suborder Unionidina Gray, 1854

Superfamily Unionoidea Rafinesque, 1820

Family Unionidae Rafinesque, 1820

Genus Proparreysia Wanner, 1921

Proparreysia sp.

Figure 2F.

Description. Medium, elongated, convex semi-triangular shell; concentric growth lines, very fine, little marked; umbo weakly inclined.

Material. Left valve, IPN-PAL 212.

Measurements. Length = 39.0 mm, width = 41.6 mm, height = 15.2 mm.

Observations. The genus is represented by several species in the Kaiparowits Formation (Campanian) of Utah (Taparila and Roberts, 2013).

Genus Unio Philipsson, 1788

Unio sp.

Figure 2G, 2H.

Description. Elongated, large, suboval shell, moderately compressed laterally, weakly marked umbons and located in the anterior third of the shell, which has fine growth lines: strongly marked hinge, with teeth and pits evident in a specimen that preserves the left leaflet. Ligament marks preserved posterior to hinge.

Material. A left valve (IPN-PAL 213) and an articulated specimen (IPN-PAL 214).

Measurements. IPN-PAL 213, length = 30.7 mm, width = 50.0 mm (Figure 2G); IPN-PAL 214, length= 40.0 mm, width = 56.9 mm (Figure 2H).

Observations. Unio is common in Mesozoic and Cenozoic freshwater deposits around the world. Although there is similarity with the specimens reported by Lucas et al. (1995) for the Cabullona de Sonora Group, the specimens of the Olmos Formation present a smoother and less compressed shell in ventro-dorsal view.

Genus Unionelloides Gu, 1962

(sensu Fang et al., 2009)

Unionelloides? sp.

Figure 2I.

Description. Globose shell, surface covered by wide concentric growth lines; small umbons, inclined almost 180 degrees with respect to the dorsal portion; anterior region almost straight, posterior rounded; ventral margin rounded to triangular; small hinge.

Material. A left valve, IPN-PAL 215.

Measurements. Length = 39.3 mm, height = 43.3 mm, width = 18.4 mm.

Observations. Although the valve shows a certain degree of deformation, the characteristics seem to coincide with the genus.

Genus Plesielliptio Russell, 1934

Plesielliptio sp.

Figure 2J-2R

Description. Medium, slightly elongated, subtriangular shell; umbons located a third of the longitudinal distance from the anterior margin; ornamentation of fine concentric lines; hinge made up of pits and teeth inclined to transversal.

Material. Eight right valves and one left. IPN-PAL 215, IPN-PAL 216, IPN-PAL 217, IPN-PAL 218, IPN-PAL 219, IPN-PAL 220, IPN-PAL 221, IPN-PAL 222 (left valve) and IPN-PAL 223.

Measurements. IPN-PAL 215, length = 21.6 mm, width = 27.9 mm (Figure 2J); IPN-PAL 216, length = 25.5 mm, width = 40.1 mm (Figure 2K); IPN-PAL 217, length = 24.8 mm, width = 31.5 mm (Figure 2L); IPN-PAL 218, Length = 20.6 mm, width = 26.5 mm (Figure 2M); IPN-PAL 219, length = 7.6 mm, width = 8.8 mm (Figure 2N); IPN-PAL 220, length = 20.2 mm, width = 25.2 mm (Figure 2O); IPN-PAL 221, length = 21.7 mm, width = 27.5 mm (Figure 2P); IPN-PAL 222 (left leaflet), length = 22.2 mm, width = 27.5 mm (Figure 2Q); IPN-PAL 223, length = 10.7 mm, width = 11.9 mm (Figure 2R).

Observations. The specimens of the Olmos Formation are similar to Plesielliptio sonoraensis Kues, in Lucas et al., 1995, but the preservation does not allow a certain specific allocation.

Suborder Ostreina Férrusac, 1822

Superfamily Ostreoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Osteidae Rafinesque, 1815

Subfamily Ostreinae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Ostrea Linnaeus, 1758

Ostrea sp.

Figure 2S.

Description. Small, flattened right valve, with some concentric growth lines.

Material. A right valve, IPN-PAL 225.

Measurements. Length = 9.5 mm, width = 6.2 mm.

Observations. Ostrea sensu stricto is a common bivalve marine environments, so it is probable that the specimen has been transported to the freshwater deposits of the Olmos Formation.

- Discussion

We found that almost all the specimens identified in the Tajo La Lulú from the Olmos Formation were related to freshwater organisms, such as Viviparus, Mesolanistes, Unio, Unionelloides?, Proparreysia, and Plesielliptio. Nevertheless, Pseudolimea and Ostrea have been recorded inhabiting a range of environments, from shallow marine sediments such as estuaries to the deep sea (Mikkelsen and Bieler, 2008). The amount of these brackish specimens was scarce compared to Unionidae. In addition the poor preservation of Pseudolimea and Ostrea, suggest that they may had been transported from the coastal or mangrove areas to the freshwater deposits of the Olmos Formation.

Unionidae has been collected in different Cretaceous assemblages of North America (Stanton, 1917; Russell, 1934; Tozer, 1956; Taylor, 1975; Hartman, 1976, 1999). Unionoids are abundant and diverse in fluvial, lacustrine, and estuarine environments. These organisms only survive under running and oxygenated water (Scholz and Hartman, 2007; Roberts et al., 2008). In the case of Unio, their species generally prefer a muddy environment with a bottom free of vegetation (Teng-Chien, 1950). This feature may indicate a minimum transport due to the usually fragile shells of Unionidae (Kotzian and Simöes, 2006). This portion of the Olmos Formation represents freshwater systems allowing the unionid community establishment.

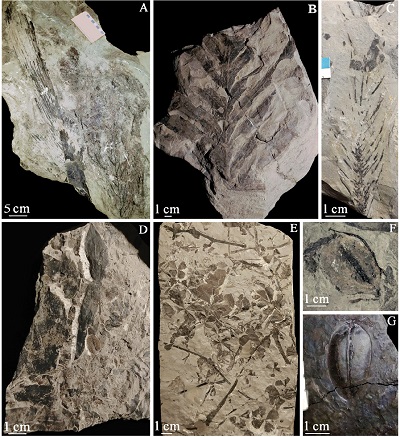

For the gastropods we found Viviparus, a relatively abundant genus in the Cretaceous and Paleocene deposits of North America (Perrilliat et al., 2008). Both Recent and fossil species of Viviparus inhabit numerous freshwater low-energy environments, founding in part buried in the mud or silt of lakes, ponds, or slower portions of streams where there is some vegetation and muddy substrate (Pace, ١٩٧٣; Van Damme, 1984; Glöer and Meier-Brook, 1998). Regarding Mesolanistes, it has been reported from river, marshes, ponds and lake deposits adjacent to the marine environment of the Upper Cretaceous of Sonora, Coahuila, and in other lithostratigraphic units from North America (e.g., Yen, 1945; Lucas et al., 1995; Perrilliat et al., 2008). In future studies, this assemblage from the Olmos Formation could be compared with the landscape to that described in the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Upper Campanian), from where Mesolanistes and Viviparus were also recorded (Lucas et al., 1995; Perrilliat et al., 2008). The Cerro del Pueblo Formation (upper Campanian) in the Parras Basin (south of the Olmos Formation outcrops) contains more diverse paleoenvironments that changed in time affected by high-frequency changes in relative sea level and coastal storm events (Eberth et al., 2004). The geographic location of the tajo La Lulú is further south of the rest of the fossiliferous outcrops in the Sabinas-Múzquiz Basin, from where different specimens of plants have been recorded (e.g. Estrada-Ruiz et al., 2018; Centeno-González et al., 2021, 2019, Figure 3). In most localities, no samples of mollusks have been found, except by a few and fragmentary specimens. These northern localities contain a high concentration of leaves and fruits related to paratropical or tropical environments, such as palms, conifers, and paratropical angiosperms (e.g., Weber, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1978; Serlin et al., 1980; Cevallos-Ferriz, 1992; Estrada-Ruiz et al., 2007, 2010, 2011; Sainz-Resendiz et al., 2015; Centeno-González et al., 2019, 2021). In addition, aquatic plants have been recorded, including ferns such as Salvinia sp. and Marsilea mascogos, linking them to stagnant freshwater bodies (Estrada-Ruiz et al., 2018). In the Tajo La Lulú, we collected fragmented and poorly preserved samples of leaves, organic matter, and a leaf that resembled a conifer (Figure 3). This suggests that this area corresponded to a transitional zone, where freshwater bodies and estuaries or marshes coexisted.

|

| Figure 3. Some specimens of the flora recorded in the Olmos Formation; A. Palm leaf; B. Fern; C. Conifer leaf; D. Angiosperm leaf and aquatic fern Salvinia sp.; E. Aquatic fern Marsilea mascogos Estrada-Ruiz et al. 2018; F, G. Two fruits, a complete capsule and other inclomplete fruit of angiosperm. |

- Conclusions

The record of freshwater bivalves and gastropods in the Olmos Formation help understand the paleoenvironments of this region during the Late Cretaceous. The identification of the two freshwater gastropods Viviparus sp. and Mesolanistes sp., allow us to assume the presence of freshwater low-energy environments, such as swamps, ponds, and streams. This is supported by the relative abundance of Unionidae (Proparreysia sp., Unio sp., Unionelloides? sp., and Plesielliptio sp.), a freshwater family that was present in fluvial, lacustrine, and estuarine environments of Cretaceous assemblages of North America. Presence of some specimens with articulated valves indicate minimum transport of this community. Additionally, we recorded Limidae (Pseudolimea sp.) and Ostreidae (Ostrea sp.), both related to marine or marshes o estuarine environments. Nevertheless, the record of these specimens was scarce and with poor preservation of the valves, indicate a possible transport derived by a storm event from the coastal or mangrove area to the freshwater deposits of the Olmos Formation. Other features are related to the record of plants present in different localities of the Olmos Formation, including the plants recollected along with the mollusk assemblage.

Contributions of authors

(1) Conceptualization: Centeno-González, N.K.; (2) analysis of data: Zúñiga-Bermúdez, G.; (3) methodologic development: Estrada-Ruiz, E.; (4) identification and description of specimens: Vega, F.J.

Financing

This research was funded by Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado – Instituto Politécnico Nacional (20230153) grant to E.E.R.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the observations made by the active searching of the mineworkers, Claudio Ayala, Ruth Zúñiga, Cuauhtémoc González†, Martín Galicia, Héctor Porras and Miguel Luna Fuentes. Our sincere gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments to imrpove the original document.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Bandel, K., Kowalke, T., 1999, Gastropod fauna of the Cameroonian coast: Helgoland Marine Research, 53, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152005 0016 46

Checa, A., Domènech, R., Gili, C., Olóriz, F., Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., 2009, Moluscos, in Martínez-Chacón, M.L., Rivas, P. (eds.), Paleontología de invertebrados: España, Sociedad Española de Paleontología, Universidad de Oviedo, Universidad de Granada, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 227–376.

Centeno-González, N.K., Porras-Múzquiz, H., Estrada-Ruiz, E., 2019, A new fossil genus of angiosperm leaf from the Olmos Formation (upper Campanian), of northern Mexico: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 91, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2019.01.016

Centeno-González, N.K., Martínez-Cabrera, H.I., Porras-Múzquiz, H., Estrada-Ruiz, E., 2021, Late Campanian fossil of a legume fruit supports Mexico as a center of Fabaceae radiation: Communications Biology, 4, 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01533-9

Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S., 1992, Tres maderas de gimnospermas cretácicas del norte de México: Anales del Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 63, 111–137.

Corona-Esquivel, R., Tritlla, J., Benavides-Muñoz, M.E., Piedad-Sánchez, N., Ferrusquia- Villafranca, I., 2006, Geología, estructura y composición de los principales yacimientos de carbón mineral en México: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 58, 141–160. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2006v58n1a5

Cox, L.R., 1959, Thoughts on the classification of the Gastropoda: Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 33, 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a064829

Cuvier, G., 1797, Tableau e´le´mentaire de l’histoire naturelle des animaux. Paris, 710 p.

Dockery, D.T., 1993, The Streptoneuran gastropods, exclusive of the Stenoglossa of the Coffee Sand (Campanian) of northeastern Mississippi: USA, Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, 191 p.

Donovan, S.K., Hensley, C., 2003, Fossils explained 45: Gastropods 1: Geology Today, 19, 223–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2451.2004.00435.x

Douglas, J.A., Arkell, W.J., 1932, The stratigraphical distribution of the Corn brash. II.The north-eastern area: Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 88, 112–170. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1932.088.01-04

Eberth, D.A., Delgado-de Jesús, C.R., Lerbekmo, J.F., Brinkman, D.B., Rodríguez de la Rosa, R., Sampson, S.D., 2004, Cerro del Pueblo Fm (Difunta Group, Upper Cretaceous), Parras Basin, southern Coahuila, Mexico: Reference sections, age, and correlation: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 21, 335–352.

Estrada-Ruiz, E., 2009, Reconstrucción de los ambientes de depósito y paleoclima de la región de Sabinas-Saltillo, Estado de Coahuila, con base en plantas fósiles del Cretácico Superior: México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tesis doctoral, 251 p.

Estrada-Ruiz, E., Centeno-González, N.K., Aguilar-Arellano, F., Martínez-Cabrera, H.I., 2018, New record of the aquatic fern Marsilea, from the Olmos Formation (upper Campanian), Coahuila, Mexico: International Journal of Plant Sciences,179, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1086/697729

Estrada-Ruiz, E., Martínez-Cabrera, H.I., Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S., 2007, Fossil wood from the late Campanian-early Maastrichtian Olmos Formation, Coahuila, Mexico: Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 145, 123–133. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.09.003

Estrada-Ruiz, E., Martínez-Cabrera, H.I., Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S., 2010, Fossil woods from the Olmos Formation (late Campanian-early Maastrichtian), Coahuila, Mexico: American Journal of Botany, 97, 1179–1194. https://doi.org/1 0.3732/ajb.0900234

Estrada-Ruiz, E., Martínez-Cabrera, H.I., Callejas-Moreno, J., Upchurch, G.R. Jr., 2013, Floras tropicales cretácicas del norte de México y su relación con floras del centro-sur de América del Norte: Polibotánica, 36, 41–61.

Estrada-Ruiz, E., Upchurch, Jr., G.R., Wolfe, J.A., Cevallos-Ferriz, S.R.S., 2011, Comparative morphology of fossil and extant leaves of Nelumbonaceae, including a new genus from the Late Cretaceous of Western North America: Systematic Botany, 32, 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364411X569525

Fang, Z.-J., Chen, J.-H., Chen, C.-Z., Sha, J.-G., Lan, X., Wen, S.-X., 2009, Supraspecific taxa of the Bivalvia first named, described, and published in China (1927–2007): USA, University of Kansas, Palaeontological Institute: Palaeontological Contributions 17, 155 p.

Férrusac, A. E. de, 1822, Tableaux systematiques des animaux mollusques: Paris, A. Bertrand, 111 p.

Fitzinger, L.I., 1833, Systematisches Verzeichnis der im Erzherzogthume Oesterreich vorkommenden Weichthiere, als Prodrom einer Fauna desselben: Beiträge zur Landeskunde Oesterreich Enns, 3, 88–122. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.10037

Flores-Espinoza, E., 1989, Stratigraphy and sedimentology of the Upper Cretaceous terrigenous rocks and coal of the Sabinas-Monclova area, northern Mexico: USA, University of Texas at Austin, Ph. Dissertation, 315 p.

Glöer, P., Meier-Brook, C., 1998, Süsswassermollusken. Deutscher Jugendbund für Naturbeobachtung: Hamburg, Visurgis Wilfried Henze, 136 p.

González-Partida, E., González-Betancourt, A.Y., Camprubí, A., Carrillo-Chávez, A., Iriondo, A., Enciso-Cárdenas, J.J., González Carrillo, F., Vázquez Ramírez, J.T., 2022, Tiempos de acumulación de carbón en México con especial énfasis en la Cuenca de Sabinas México, donde se proporcionan nuevos datos geocronológicos: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 39(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.22201/cgeo.20072902e.2022.3.1704

Gray, J.E., 1842, Synopsis of the contents of the British Museum. (44th edition): London, British Museum, 308 p.

Gray, J.E., 1847, A list of the genera of Recent Mollusca, their synonyma and types. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 15, 129–242.

Gray, J.E., 1854, A revision of the arrangement of the families of bivalve shells (Conchifera): Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 13(2), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03745485709496364

Gu, Z.-W., 1962, Jurassic lamellibranches, in Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (eds.), Handbook of Index Fossils in Yangtze Region: Beijing, Science Press, 148–149.

Hartman, J.H., 1976, Uppermost Cretaceous and Paleocene nonmarine Mollusca of eastern Montana and southwestern North Dakota.: USA,University of Minnesota, MS thesis, 216 p.

Hartman, J.H., 1999, Western exploration along the Missouri River and the first paleontological studies in the Williston Basin, North Dakota and Montana, in Hartman, J. H., (ed.), The paeontological and geological record of North Dakota—Important sites and current interpretations: Proceedings North Dakota Academy of Sciencies, 53, 158–165.

Kotzian, C.B., Simöes, M.G., 2006, Taphonomy of recent freshwater molluscan death assemblages, Touro Passo stream, southern Brazil: Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 9, 243–260. https://doi.org/10.4072/rbp.2006.2.08

Linnaeus, C., 1758, Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 10 edition, reformata: Stockholm, Laurentius Salvius. http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/no_cache/dms/load/toc/?IDDOC=265100

López-Conde, O.A., Pérez-García, A., Chavarría-Arellano, M.L., Alvarado-Ortega, J., 2021, A new bothremydid turtle (Pleurodira) from the Olmos Formation (upper Campanian) of Coahuila, Mexico: Cretaceous Research, 119, 104710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104710

Lucas, S.G., Kues, B.S., González-León, C.M., 1995, Paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Cabullona Group, northeastern Sonora, in Jacques-Ayala, C., González-León, C.M., Roldán-Quintana, J. (eds.), Studies on the Mesozoic of Sonora and Adjacent Areas: USA, Geological Society of America Special Paper, 301, 143–165p.

Meyer, C.A., Frey, E.D., Thüring, B., Etter, W., Stinnesbeck, W., 2005, Dinosaur tracks from the Late Cretaceous Sabinas basin (Mexico): Kaupia. Darmstädter Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte, 14, 41–45.

Mikkelsen, P.M., Bieler, R., 2008, Seashells of Southern Florida: Bivalves. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 503 p.

Montfort, D., 1810, Conchyliologie systematique et classification méthodique des coquilles. Volume 1. Paris: Coquilles univalves, cloisonneés, 409 p.

Newell, N.D., 1965, Classification of the Bivalvia: American Museum Novitates, 2205, 1–25.

Ojeda-Rivera, J., Delgado-Hernández, J., Villamar, S., 1968, Coal geology of the Sabinas Basin, Coahuila: USA, Geological Society of America, Fieldtrip Guidebook, Series 11, 72p.

Pace, G.L., 1973, The freshwater snails of Taiwan (Formosa): Malacological Review, 1, 1–117.

Perrilliat, M.C., Vega, F., Espinosa, B., Naranjo-García, E., 2008, Late Cretaceous and Paleogene freshwater gastropods from Northeastern Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 82, 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1666/06-062.1

Philipsson, L.M., 1788, Dissertatio Historico-naturalis Sistens Nova Testaceorum Genera, in Retzius, A. (ed.), Ad publicum examen defert Laurentius Münter Philipsson: Berlingianis: Lunda, 28 p.

Porras-Múzquiz, H.G., Lehman, T.M., 2011, A ceratopsian horncore from the Olmos Formation (early Maastrichtian) near Múzquiz, Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 28, 262–266.

Quiroz-Barroso, S., Perrilliat, M.C., 1997, Pennsylvanian Nuculoids (Bivalvia) from the Ixtaltepec Formation, Oaxaca, Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 71, 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000039421

Rafinesque, C.S., 1815, Analyse de la naturae, ou Tanleau de l´univers et des corps organisés: Palermo, Aux dépens de l’auteur, 224 p.

Rafinesque, C.S., 1820, Monographie des coquilles bivalves fluviatiles de la Rivière Ohio, contenant douze genres et soixante-huit espèces: Annales Générales de Sciences Physiques de Bruxelles, 5, 287–322.

Ramírez-Velasco, A.A., Hernández-Rivera, R., Servín- Pichardo, R., 2014, The hadrosaurian record from Mexico, in Eberth, D.A., Evans, D.C. (eds.), Hadrosaurs: USA, Indiana University Press, 340–360.

Reid, D.G., Dyal, P., Lozouet, P., Glaubrecht, M., Williams, S.T., 2008, Mudwhelks and mangroves: The evolutionary history of an ecological association (Gastropoda: Potamididae): Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 47, 680–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.003. PMID 18359643

Robeck, R.C., Pesquera, V.R., Ulloa, A.S., 1956, Geología y depósitos de carbón de la región de Sabinas, Estado de Coahuila, en XX Congreso Geológico Internacional, México, 109 p.

Roberts, E.M., Tapanila, L., Mijal, B., 2008, Taphonomy and sedimentology of storm-generated continental shell beds: A case example from the Cretaceous Western Interior Basin: The Journal of Geology, 116, 462–479. https://doi.org/ 10.1086/590134.

Russell, L.S., 1934, Reclassification of the fossil Unionidae (fresh-water mussels) of western Canada: Canadian Field Naturalist, 48, 1–4.

Sainz-Resendiz B.A., Estrada-Ruiz, E., Mateo-Cid, L.E., Porras-Múzquiz, H., 2015, Primer registro de un estípite de Coryphoideae: Palmoxylon kikaapoa de la Formación Olmos del Cretácico Superior, Coahuila, México: Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 86, 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2015.09.009

Schmidt, A., 1855, Der Geschlechtsapparat der Stylommatophoren in taxonomischer Hinsich: Abhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereines fuer Sachsen und Thueringen in Halle, 1, Berlin, 52 p.

Scholz, H., Hartman, J.H., 2007, Fourier analysis and the extinction of unionoid bivalves near the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary of the Western Interior, USA: Pattern, causes, and ecological significance: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 255, 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.02.040

Serlin, B., Delevoryas, T., Weber, R. 1980. A new conifer pollen cone from the upper Cretaceous of Coahuila, Mexico: Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 31, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-6667(80)90029-9

Silva-Bárcenas, A., 1969, Localidades de vertebrados fósiles en la República Mexicana: Paleontología Mexicana, 28, 1-34.

Smitha, S., Mustak, M.S., 2017, Gastropod diversity with physico-chemical characteristics of water and soil in selected areas of Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka, India: International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies, 4, 15–21.

Stanley, Jr. G.D., González, C., Sandy, M.R., Senowbari, B., Doyle, P., Tamura, M., Erwin, D.H., 1994, Upper Triassic Invertebrates from the Antimonio Formation, Sonora, Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 36, 26-27. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S0022336000062284

Stanton, T.W., 1917, Nonmarine Cretaceous Invertebrates of the San Juan Basin: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, 98-R, 309–326.

Taylor, D.W., 1975, Early Tertiary mollusks from the Powder River Basin, Wyoming-Montana, and adjacent regions: U.S. Geological Survey, Open File Report. 75–331, 551 p.

Taparila, L., Roberts, E.M., 2013, Continental invertebrates and trace fossils from the Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, Utah, in Titus, A.L., Loewen, M.A. (eds.), At the top of the grand staircase; The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah: USA, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 132-151.

Teng-Chien, Y., 1950, Fresh-Water Mollusks of Cretaceous Age from Montana And Wyoming: Geological Survey Professional Paper, 233-A, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp233A

Torres-Rodríguez, E., Montellano-Ballesteros, M., Hernández-Rivera, R., Benammi, M., 2010, Dientes de terópodos del Cretácico Superior del Estado de Coahuila, México: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 27, 72–83.

Tozer, E.T., 1956, Uppermost Cretaceous and Paleocene non-marine molluscan faunas of western Alberta: Geological Survey of Canada, 280, 1–125.

https://doi.org/10.4095/101507

Van Damme, D., 1984, The Fresh-water Mollusca of Northern Africa. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 164 p.

Vega, F.J., Naranjo-García, E., Aguillón, M.C., Posada-Martínez, D., 2019, Additions to continental gastropods from the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene of NE Mexico: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 71, 169–191. https: //doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2019v71n1a9

Vega, F.J., Perrilliat, M.C., 1990, Moluscos del Maastrichtiano de la sierra El Antrisco estado de Nuevo León: Paleontología Mexicana, 55, 1–65.

Wanner, H.E., 1921, Some faunal remains from the York County, Pennsylania: Proceedings of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, 73(1), 25-37.

Weber, R., 1972, La vegetación Maestrichtiana de la Formación Olmos de Coahuila, México. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 33, 5–19. https: //doi.org/10.18268/bsgm1940v10n9a2

Weber, R., 1973, Salvinia coahuilensis nov. sp. del Cretácico Superior de México: Ameghiniana, 10, 173–190.

Weber, R., 1975, Aachenia knoblochi nov. sp. an interesting conifer of the upper Cretaceous Olmos Formation of Northeastern Mexico: Palaeontographica Abteilung B, 152, 76–83.

Weber, R., 1978, Some aspects of the Upper Cretaceous angiosperms, flora of Coahuila, Mexico: Courier Forschungs-Institut Senckenberg, 30, 38–46.

Yen, T.C., 1945, Notes on a Cretaceous Fresh-Water Gastropod from southwestern Utah: Notulae Naturae of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 160, 1–3.

Peer Reviewing under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-SA license(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/)