|

BOLETÍN DE LA SOCIEDAD GEOLÓGICA MEXICANA http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2011v63n3a2 |

|

Presence of a maniraptoriform dinosaur in the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Chiapas, southern Mexico

Presencia de un dinosaurio maniraptoriforme en el Cretácico tardío (Maastrichtiano) de Chiapas, sur de México

Gerardo Carbot–Chanona1,* y Héctor E. Rivera–Sylva2

1 Museo de Paleontología "Eliseo Palacios Aguilera", Dirección de Paleontología, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente e Historia Natural. Calzada de los Hombres Ilustres s/n, 29000, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México.

2 Departamento de Paleontología, Museo del Desierto, Carlos Abedrop Dávila 3745, 25022, Saltillo, Coahuila, México.

*This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

Here is described the first dinosaur evidence from Chiapas, and also the southernmost evidence of dinosaurs in Mexico. A small theropod tooth, identified as Richardoestesia isosceles, based on its shape and the presence of small denticles on the mesial and distal carinae with rounded outline, was collected in the Ocozocoautla Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian). These results extend the fossil record of this taxon in North America, as it is the southernmost record of Richardoestesia and the first report of this genus in Mexico.

Keywords: Dinosaur, Theropoda, Richardoestesia, Maastrichtian, Chiapas, Mexico.

Resumen

Se describe la primera evidencia de dinosaurios para Chiapas, que también es la evidencia más sureña de dinosaurios en México. Un pequeño diente de terópodo, identificado como Richardoestesia isosceles, basado en la forma del diente y la presencia de pequeños dentículos con contorno redondeado en las carenas mesial y distal, fue colectado en la Formación Ocozocoautla (Cretácico Tardío, Maastrichtiano). Los resultados extienden el registro fósil de este taxón en América del Norte, siendo el registro más sureño de Richardoestesia, así como el primer registro de este género en México.

Palabras clave: Dinosaurio, Theropoda, Richardoestesia, Maastrichtiano, Chiapas, México.

1. Introduction

In Mexico, several localities with dinosaur remains have been found principally in the central and northern part of the country. Bones, teeth and footprints of dinosaurs come from Baja California, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Puebla and Oaxaca (Rivera–Sylva et al., 2006). The southernmost record of dinosaurs in Mexico is from Chiapas. Carbot–Chanona and Avendaño–Gil (2002) mention the "raptor" theropod tooth from Ocozocoautla Formation (Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous) in a preliminary report on Chiapas. In this paper we describe in detail the specimen and assign it to the genus Richardoestesia, a maniraptoriform dinosaur first described from the Campanian Judith River Formation (Currie et al., 1990). The fossil record of Maniraptoriformes in Mexico is rather scarce, apart from the material from El Gallo Formation in Baja California (Hernández–Rivera,1997), the Aguja Formation in Chihuahua (Weishampel et al., 2004), and the Cerro del Pueblo Formation in Coahuila (Torres–Rodríguez et al., 2010). The only genus recognized in these localities is Saurornitholestes, and this is only documented by teeth. Therefore, the presence of the genus Richardoestesia is new for Mexico.

2. Geological and paleontological setting

The Ocozocoautla Formation is a stratigraphic sequence of carbonate sediments that was deposited during the Late Cretaceous in southeast Mexico (Feldmann et al., 1996). Underlying this unit are the limestones from the Sierra Madre, which are Early to Middle Cretaceous in age (Steele and Waite, 1986), and above it lies the Soyaló Formation, from the Paleocene (Ferrusquía–Villafranca, 1996). The Ocozocoautla Formation is approximately 630 m thick, and is formed of red and brown prodeltaic sandstones and some conglomerates at its base (Figure 1). Towards the upper part of the formation the lithology changes to shales, marls, and limestones that are beige in color (Frost and Langenheim, 1974; Gutiérrez–Gil, 1956). The lithology changes laterally within the formation indicating that the environment of deposition changed from a shallow lagoon environment to very deep waters (Vega et al., 2001).

The marine invertebrate fauna of the Ocozocoautla Formation is very similar to that of other regions of the Late Cretaceous such as Jamaica, Cuba, Guatemala and Saint Croix (Vega et al., 2001). Some limestone layers in the Ocozocoautla Formation have abundant foraminifers, corals, rudists, gastropods, crabs and indeterminate ostracods (Alencáster, 1971; Filkorn et al., 2005; Omaña, 2006; Puckett et al., 2010; Vega et al., 2001). The vertebrate fauna included sharks (González–Barba et al., 2001), indeterminate turtles and one gavialoid crocodile (Carbot–Chanona, 2009).

The Maastrichtian age is consistent for the Ocozocoautla Formation, based mainly on the stratigraphic ranges of corals, rudists, crabs and planktonic foraminifers found there.

3. Material and methods

The specimen comes from a vertebrate microfossil site in the Ocozocoautla Formation. The tooth was collected by surface collection. The specimen is housed in the Museo de Paleontología "Eliseo Palacios Aguilera", where detailed locality information is on file.

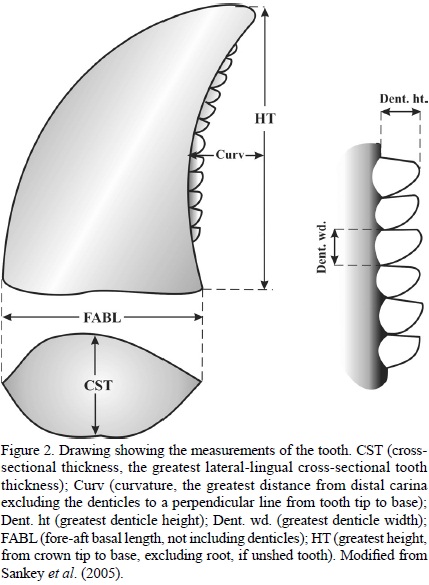

Location of tooth measurements are illustrated in Figure 2. A stereoscopic microscope with an ocular micrometer was used. Measurements are given in millimeters (mm) and are abbreviated as follows: FABL, fore–aft basal length; HT, height; Curv, curvature; CST, cross–sectional thickness; CSS, cross–sectional shape; and dent/mm, denticles/mm.

Institutional abbreviations: IHNFG, Instituto de Historia Natural, Geographic Collection.

4. Systematic paleontology

Order Saurischia Seeley, 1888

Suborder Theropoda Marsh, 1881

Infraorder Maniraptora Gauthier, 1986

Genus Richardoestesia Currie, Rigby and Sloan, 1990

Richardoestesia isosceles Sankey, 2001

Type species: Richardoestesia gilmorei Currie, Rigby and Sloan, 1990

Original diagnosis: Teeth straight, narrow, shaped like an isosceles triangle in lateral view. Shape of tooth in basal cross–section is labio–lingually flattened oval. Denticles minute (0.1 mm in height and in anteroposterior width), square, uniformly–sized from base to tip of tooth; extended length of carine. Anterior denticles, if present, often considerably smaller than posterior denticles. Interdenticle spaces usually minute and barely visible; denticles closely spaced. Denticle tips straight or faintly rounded, but not pointed; 7–11 denticles per millimeter (Sankey, 2001).

4.1. Material

IHNFG–0537, isolated maxilar tooth.

4.2. Horizon and locality

Ocozocoautla Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian), Ocozocouatla, Chiapas, southern Mexico.

4.3. Description

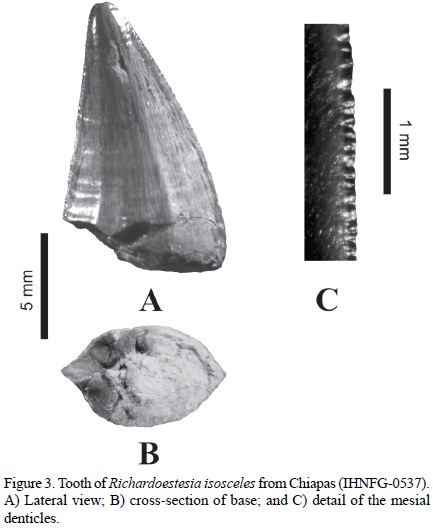

Small tooth, triangular in shape, with the mesial border slightly curved; labio–lingually flattened oval in cross section. Small denticles present on mesial and distal carinae. The mesial denticles are much more distinct than the distal, and generally 7 to 9 denticles per millimeter are present; denticles are 0.13–0.17 mm wide and 0.13–0.2 mm high. The denticles are approximately uniform in size from halfway to the tip of tooth, but are not observed near the base. The denticles are nearly square, with rounded outline. Interdenticle spaces are not present (Figure 3, Table 1).

5. Discussion

Among all Late Cretaceous theropods, Richardoestesia is the genus with the smallest denticles in its teeth. Currently, two species of Richardoestesia are recognized, R. gilmorei and R. isosceles. Richardoestesia gilmorei was erected upon some teeth from the Judith River Formation by Currie et al. (1990), and R. isosceles was erected later by Sankey (2001), based on isolated teeth from the Aguja Formation in Texas. Sankey et al. (2002) noted that Richardoestesia gilmorei and R. isosceles differ in the curvature of the proximal part of the tooth. Tooth shape of R. gilmorei is more strongly recurved and resembles the teeth of Saurornitholestes, while in R. isosceles the tooth shape resembles an isosceles triangle. The shape of IHNFG–0537 is more similar to that of R. isosceles than that of R. gilmorei. The denticles in R. gilmorei are pointed, and interdenticles spaces are present, whereas in R. isosceles denticles are present along both edges, and are not pointed (Sankey et al., 2005), as seen in IHNFG–0537. All the morphological characteristics suggest that the tooth described in this paper belongs to Richardoestesia isosceles.

Longrich (2008) considered there to be only one species of Richardoestesia, and further considered Paranychodon to be a junior synonym (the difference being variation associated with heterodont dentition). But until more material is found, we have assigned specimen IHNFG–0537 to Richardoestesia isosceles, following Larson (2008), who mentions contradictions to a monospecific Richardoestesia.

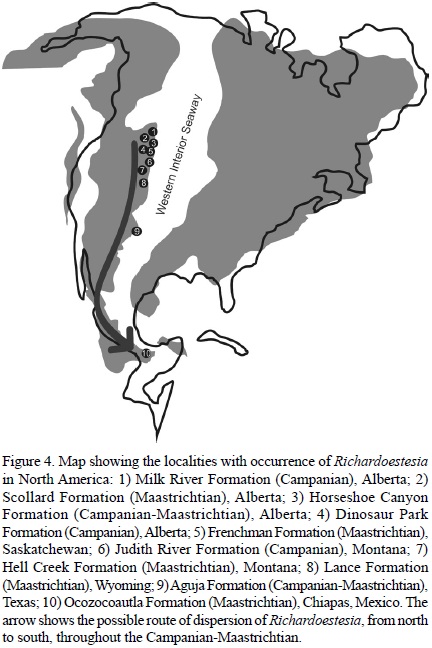

Richardoestesia has been identified in the Milk River Formation, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, the Scollard Formation and the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta; the Frenchman Formation in Saskatchewan; the Judith River Formation in Montana; the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota; the Lance Formation in Wyoming; and in the Aguja Formation in Texas (Currie et al., 1990; Baszio, 1997; Sankey, 2001). Prieto–Márquez et al. (2000) reported Richardoestesia based on a tooth from the Pyrenees, Spain. As for Mexico, this is the first report of the genus. The record for Chiapas extends considerably the geographic range of Richardoestesia, becoming the southernmost record in North America by almost two thousand kilometers.

Several authors have suggested that the central region of Chiapas was completely covered with a shallow sea during the Late Cretaceous (e.g. Filkorn et al., 2005; Vega et al., 2001). However, the presence of Richardoestesia in Chiapas considerably changes the perception previously held regarding this region of the country, since it suggests the existence of continental zones connections to northern Mexico, the United States and Canada (Figure 4). Possibly, the continental areas were close to the coast line, as suggested by the vertebrate nonmarine taxa found in the Ocozocoautla Formation (crocodiles and turtles). This kind of environment also agrees with the kind of lifestyle proposed by Baszio (1997), who suggests that Richardoestesia had a piscivorous diet on account of the small and punctuated shape of its teeth, features that occur in long–snouted piscivores. The wear pattern of Richardoestesia teeth is also consistent with piscivory (Longrich, 2008).

6. Conclusions

Based on the comparison of the tooth IHNFG–0537 from the Ocozocoautla Formation with teeth from other Late Cretaceous localities in North America described by Currie et al. (1990) and Sankey (2001), we identify it as the genus Richardoestesia. This is the southernmost record of the genus for North America. The presence of dinosaurs in Chiapas suggests a near–shore environment, in contrast to the previously held idea of the region being a shallow sea, reinforcing the suggestion that Richardoestesia had a piscivorous life style.

Acknowledgements

We thank José Rubén Guzmán–Gutiérrez for providing bibliography, and Marco A. Coutiño–José and Javier Avendaño–Gil for their support during the field seasons. The material described here was rescued thanks to financial aid provided by the government of Chiapas, through the project "Rescate del Patrimonio Paleontológico de la carretera Ocozocoautla–Cosoleacaque, Chiapas". We also thank Thomas Holtz (University of Maryland), Don Brinkman (Royal Tyrell Museum) and José Ignacio Canudo (Universidad de Zaragoza) for their reviews and helpful comments that improved this manuscript, and Francisco Sour (Museo de Paleontología, UNAM) for his support in the editorial process.

References

Alencáster, G., 1971, Rudistas del Cretácico Superior de Chiapas, Parte I: Paleontología Mexicana, 34, 1–91.

Baszio, S., 1997, Systematic paleontology of isolated dinosaur teeth from the Latest Cretaceous of south Alberta, Canada: Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, 196, 33–77.

Carbot–Chanona, G., 2009, Una nueva especie de gavial primitivo del Maastrichtiano de Chiapas y su significación paleobiogeográfica (abstract), in XI Congreso Nacional de Paleontología: Juriquilla, Querétaro, Sociedad Mexicana de Paleontología, 12.

Carbot–Chanona, G., Avendaño–Gil, M.J., 2002, Dinosaurios en Chiapas: Revista de la Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas, 4, 99–107.

Currie, P.J., Rigby Jr., J.K., Sloan, R.E., 1990, Theropod teeth from the Judith River Formation of southern Alberta, Canada, in Carpenter, K., Currie, P.J. (eds.), Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives: Cambridge, U.K., Cambridge University Press, 107–125.

Feldmann, R.M., Vega, F., Tucker, A.B., García–Barrera, P., Avendaño, J., 1996, The oldest record of Lophoranina (Decapoda: Raninidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Chiapas, southeastern Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 70, 296–303.

Ferrusquía–Villafranca, I., 1996, Contribución al conocimiento geológico de Chiapas — el área Ixtapa–Soyaló: Boletín del Instituto de Geología UNAM, 109, 1–130.

Filkorn, H.F., Avendaño–Gil, J., Coutiño–José, M.A., Vega–Vera, F.J., 2005, Corals from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Ocozocoautla Formation, Chiapas, Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 22, 115–128.

Frost, S.H., Langenheim, R.L., 1974, Cenozoic reef biofacies; Tertiary larger foraminifera and scleractinian corals from Chiapas, Mexico: DeKalb, Illinois, U.S.A., Northern Illinois University Press, 388 p.

Gauthier, J., 1986, Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds: California Academy of Science Memoirs, 8, 1–55.

González–Barba, G., Coutiño, M.A., Ovalles–Damián, E., Vega–Vera, F.J., 2001, New Maastrichtian elasmobranch faunas from Baja California Peninsula, Nuevo León and Chiapas state, Mexico (abstract), in Tintoti A., Arriata, G. (eds.), III Internacional Meeting on Mesozoic Fishes: Systematic, Paleoenvironments and Biodiversity: Serpiano–Monte San Giorgio, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 33.

Gutiérrez–Gil, R., 1956, Geología del Mesozoico y estratigrafía pérmica del Estado de Chiapas, in XX Congreso Geológico Internacional, Guidebook, Excursion C–15: Mexico, D.F., 1–82.

Hernández–Rivera, R., 1997, Mexican dinosaurs, in Currie, P., Padian, K. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: New York, Academic Press, 433–437.

Larson, D.W., 2008, Diversity and variation of theropod dinosaur teeth from the uppermost Santonian Milk River Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Alberta: a quantitative method supporting identification of the oldest dinosaur tooth assemblage in Canada: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 45, 1455–1468.

Longrich, N., 2008, Small theropod teeth from the Lance Formation of Wyoming, USA, in Sankey, J.T., Baszio, S. (eds.), Vertebrate microfossil assemblages: their role in paleoecology and paleobiogeography: Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 135–158.

Omaña, L., 2006, Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) foraminiferal assemblage from the inoceramid beds, Ocozocoautla Formation, central Chiapas, SE Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 23, 125–132.

Prieto–Márquez, A., Gaete, R., Galobart, A., Ardevol, L., 2000, A Richardoestesia–like theropod tooth from the Late Cretaceous foredeep, south–central Pyrenees, Spain: Eglogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 93, 497–501.

Puckett, T.M., Arnett, B., Carbot–Chanona, G., 2010, Paleobiogeographical and plate tectonic significance of Late Cretaceous Ostracodes (Crustaceans) from Chiapas, Mexico (abstract), in 87th Annual Meeting of the Alabama Academy of Science: Alabama, Alabama A&M University Normal, 68.

Rivera–Sylva, H.E., Rodríguez–De La Rosa, R., Ortiz–Medieta, J.A., 2006, A review of the dinosaurian record from Mexico, in Vega, F.J, Nyborg, T.G., Perrilliat, M.C., Montellano–Ballesteros, M., Cevallos–Ferriz, S.R.S., Quiroz–Barroso, S.A. (eds.), Studies on Mexican paleontology: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Springer, 233–248.

Sankey, J.T., 2001, Late Campanian southern dinosaurs, Aguja Formation, Big Bend, Texas: Journal of Paleontology, 75, 208–215.

Sankey, J.T., Brinkman, D.B., Guenther, M., Currie, P.J., 2002, Small theropod and bird teeth from the Judith River Group (late Campanian), Alberta: Journal of Paleontology, 76, 751–763.

Sankey, J.T., Standhardt, B.R., Schiebout, J.A., 2005, Theropod teeth from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian–Maastrichtian), Big Bend National Park, Texas, in Carpenter, K. (eds.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs: Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 127–152.

Steele, D.R., Waite, L.E., 1986, Contributions to the stratigraphy of the Sierra Madre Limestone (Cretaceous) of Chiapas, México: Boletín del Instituto de Geología UNAM, 102, 1–175.

Torres–Rodríguez, E., Montellano–Ballesteros, M., Hernández–Rivera, R., Benammi, M., 2010, Dientes de terópodos del Cretácico Superior del estado de Coahuila, México: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 27, 72–83.

Vega, F.J., Feldmann, R.M., García–Barrera, P., Filkorn, H., Pimentel, F., Avendaño, J., 2001, Maastrichtian crustacean (Brachyura: Decapoda) from the Ocozocuautla Formation in Chiapas, southeast Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 75, 319–329.

Weishampel, D.B., Barrett, P.M., Coria, R., Le Loeuff, J., Xing, X., Xijin, Z., Gomani, E.M. P., Noto, C.R., 2004, Dinosaur Distribution, in Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H. (eds.), The Dinosauria: Berkeley, California, University of California Press, 517–606.

Manuscript received: February 24, 2011.

Corrected manuscript received: June 17, 2011.

Manuscript accepted: June 20, 2011.